At some point a while back I decided that I was going to write the front end of Weaver in Rust. I'd looked through the various 'fullstack' web application frameworks kicking around, and while they still had a ways to go, they seemed complete enough. Plus I wanted to write a semi-custom Markdown parser and renderer, to support features I wanted to exist in Weaver, like atproto record embeds, dual-column mode, and resizable images, and since I also wanted it to be fast, that meant that at least a portion of the front-end codebase would be in Rust, and Javascript-Rust FFI wasn't something I had dealt with a lot yet.

We do these things not because they were easy, but because we thought they would be easy

What I hadn't realized at the time was that none of those frameworks contained a proper editor component, at least not one that could support more than just simple text input. Which meant I either needed to change tactics and use a Javascript library for my editor, or write one. If you know me, you know which I was always going to choose, here.

Browsers are cursed

For such a foundational component of the modern way of doing UI, browsers have remarkably limited support for editing in some ways, particularly rich text input. Your batteries-included choices are basically <input> or <textarea>, both of which limit you in a bunch of ways (and the option for a formatted text input with those is to more or less make the original one invisible and then render the output on top of it, which requires syncing several bits of state, or putting the contenteditable property on another element, which requires that you reinvent the universe of editing, because you get almost nothing and the browser fights you at every turn. In Javascript, there are a number of libraries that handle this problem for you, with varying degrees of success. Codemirror, Prosemirror, Tiptap, and others. Some do the contenteditable thing, others the hidden textarea. As far as I could tell, as of when I started working on the actual editor component for Weaver a bit over a week ago, no such libraries existed for Rust. The underlying structures for text documents existed, I had a plethora of options there, but if I wanted an in-browser text editor that could do the kinds of things I needed it to do, I was going to need to write one.

Dioxus

Unfortunately Dioxus made this a little harder than one might expect. Because while it uses webview and web tools, even on native, by default, it is much more like React Native than React, in that it's meant for writing something you install as much as something you go to a website for. And where Dioxus's devs can't find enough commonality between the disparate platforms it runs on to create a common ground of functionality, it kind of just says "cast it to the underlying platform type and have fun". Which isn't the worst option out there, by a long shot, they could have simply not given you that escape hatch, but especially on the web, it means getting a lot more into the guts of browser APIs than I expected I'd have to out of the gate. So, having been through this, here's what an in-browser rich text editor, at least one built around contenteditable, looks like.

The Document Object Model

I'm going to start simple, because unironically I didn't know a lot of this a week and change ago, at least not as intimately as I do now, and for the benefit of those who aren't familiar. Web browsers expose the structure of the current web page to programming languages (primarily JavaScript, but via WebAssembly and an appropriate runtime, to any other language) via what is officially called the Document Object Model. Like many things involving the web, there is a lot of legacy stuff here. Browsers avoid breaking backward compatibility if at all possible, so there are a lot of things in the DOM and a lot of things about how it works, that are very much a product of the early 2000s. The DOM is a tree structure, with each nested group of elements forming branches and ultimately leaves of that tree, the leaves being the text nodes (and other nodes without children) that contain the final content displayed. This is actually great for querying structurally. If you want all nodes with a certain class, you can query for that. If you want a specific node, you can get it and manipulate it, whatever it contains. The problem comes when you need to translate from that structure to another one with a different structure, in my case, a Markdown document.

Markdown

Weaver uses Markdown for its internal document representation. Specifically, it intends to implement (and has a full implementation of the parser for and a partial implementation of the final renderer for) a variant of Obsidian-flavoured Markdown. This is partially because of its initial genesis as a way for me to not pay Obsidian a bunch of money per month to host vaults publicly and instead turn them into a static site I could put up anywhere, but also for the same reason Obsidian (and GitHub, and Tangled, and many other tools) uses Markdown. That reason is that it's at its heart plain text. You don't need anything special to read it easily. You can write it with any editor you want. But it has enough formatting syntax to produce reasonable documents for digital use. It's more limited than Word or LibreOffice or Google Docs internal format (honestly this whole endeavour has given me a ton of respect for the engineers behind Google Docs, as it worked damn near flawlessly from the get-go, when browsers and web technologies were quite a bit worse), much more limited than PDF, but it serves its purpose well and its simplicity is why it's still readable plain text at all.

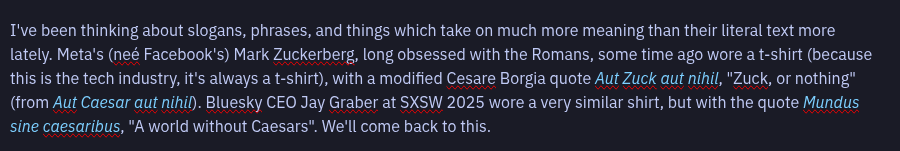

However, a flat unicode plaintext buffer and the event iterator the parser produces from it doesn't exactly map nicely onto a tree graph structure as far as indexing goes. If my cursor is at the 1240th character in the file, what DOM node does that map to? Does it have text I can put the cursor on? And within the editor it's even worse, as we conditionally show or hid things like the formatting syntax characters depending on how close your cursor is to them, so we need to keep those character's we'd normally discard in the rendered output and treat them differently. And we can't just iterate over potentially the entire document or down the tree every time we need to move the cursor or add a character, even on a modern computer that ends up being nontrivial. This is, as I understand it, a large reason why block-based editors are the dominant paradigm on the web. Leaflet's editor works this way, as does Notion, and many many more besides.

However, a flat unicode plaintext buffer and the event iterator the parser produces from it doesn't exactly map nicely onto a tree graph structure as far as indexing goes. If my cursor is at the 1240th character in the file, what DOM node does that map to? Does it have text I can put the cursor on? And within the editor it's even worse, as we conditionally show or hid things like the formatting syntax characters depending on how close your cursor is to them, so we need to keep those character's we'd normally discard in the rendered output and treat them differently. And we can't just iterate over potentially the entire document or down the tree every time we need to move the cursor or add a character, even on a modern computer that ends up being nontrivial. This is, as I understand it, a large reason why block-based editors are the dominant paradigm on the web. Leaflet's editor works this way, as does Notion, and many many more besides.

And we end up with an additional layer of complexity still, because our Markdown parser is byte-indexed, our internal document representation is unicode character grouping indexed, and then characters in the DOM are utf-16 byte-indexed. For basics like alphanumeric characters, those all line up. But for non-Latin characters, or for emoji, this breaks down rapidly. So we build up a mapping as we go.

Sample Mapping

Source:

| foo | bar |

Bytes: 0 2-5 7-10 12

Chars: 0 2-5 7-10 12 (in this case, we're in the first byte of utf-8, where it's same as ascii, so these are the same)

Rendered:

foobar

Mappings:

{ byte_range: 0..2, char_range: 0..2, node_id: "t0-c0", char_offset_in_node: 0, utf16_len: 0 }- "| " invisible{ byte_range: 2..5, char_range: 2..5, node_id: "t0-c0", char_offset_in_node: 0, utf16_len: 3 }- "foo" visible{ byte_range: 5..7, char_range: 5..7, node_id: "t0-c0", char_offset_in_node: 3, utf16_len: 0 }- " |" invisible- etc.

Mapping in hand, we can then query the DOM for the node closest to our target and then offset from there into the text node containing the spot we need to put the cursor, or the next closest one (or vice versa, when updating our internal document cursor from the DOM). Getting this bidirectional mapping to behave properly and reliably so that the cursor goes where you expect and puts text where it appears to be has been one of the largest challenges of this process, and there are still a number of weird edge cases (for example, I have composed the code blocks in this article elsewhere and pasted them in, as working with them within the editor is still extremely buggy).

Rendering (and re-rendering)

The initial version of the Weaver editor essentially re-rendered the entire editor content <div> on every cursor movement or content change. This wasn't sustainable but it worked enough to test. Rapidly I moved to something more incremental, caching previous renders, and then updating the DOM for only the paragraph which had changed, only re-rendering more of the document if paragraph boundaries had changed. Iterating over the text is fast, pulldown-cmark is an excellent library and my fork of it, required to add some of the additional features, avoids compromising its performance, but even there I avoid iterating over more than the current paragraph if possible. Updating the DOM at a paragraph level of granularity is less precise than many JS libraries, and it's possible that I will do more fine-grained diffing of the DOM over time to improve performance further, but for now it is acceptable for reasonably-sized documents, and it is the natural way to split up the document.

IME: Input Management 'Ell

Things got an order of magnitude more difficult when I started working on non-desktop keyboard input. While I'm not really targeting mobile, certainly not for the editor, I think people who compose extended WattPad stories on their phones are nuts and going to get the weirdest RSI, I do want to support other languages as well as I can, and there are well over a billion people on the planet who write in languages that use an IME to enter text, even on desktop. And of course, if someone wants to make a quick edit to a post on their phone or use a tablet to write from, they should be able to do so without it breaking the entire experience. Unfortunately, IMEs and software keyboards put text into the browser in a very different way from PC hardware keyboards. They use entirely different events, which are to some degree platform-specific, and certainly have platform-specific quirks. Read through the Prosemirror source code for input handling and see the sorts of weird stuff you need to account for. This can get extremely cursed, as you can see below, because we are well outside of stuff Dioxus helps with at this point. At some point I will figure out a better way to handle this, but for now, observe the following, derived from one of Prosemirror's workarounds:

// Android backspace workaround: let browser try first,

// check in 50ms if anything happened, if not execute fallback

let mut doc_for_timeout = doc.clone;

let doc_len_before = doc.len_chars;

let window = window;

if let Some = window

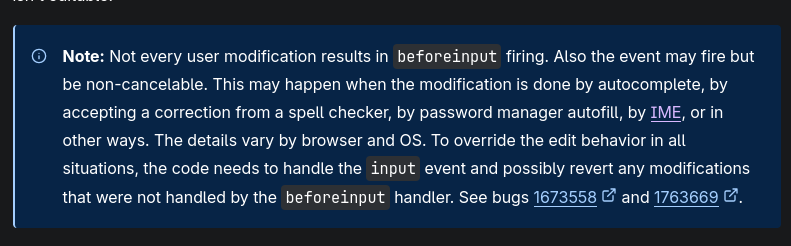

There are some alternatives, using newer browser APIs, which alleviate some of this. I currently have fewer weird platform-specific hacks in part because of swapping to using the beforeinput event as the primary means of accepting input, at suggestion of someone on Bluesky. It does seem to be consistently more reliable. However, it is far from a complete solution to this problem, as you can see if you try out the editor (please, report bugs if you do, I really appreciate it). This is also why cursor stuff is hard. Because not only are we mapping DOM to linear text document, we are also having to deal with the fact that the browser doesn't always give us the cursor information correctly, and the ways in which the cursor information, along with any other input information, we get differs from what we (and presumably the user) wants differs in ways that vary by OS and by browser, and this is worse on mobile. It's worst on Android, because different keyboards act differently.

Journey Before Destination

Pulling this all together has been challenging and educational. I hope it's useful.

Library Usage

I rarely solve a problem just for me. Because if I have a problem, I imagine I'm rarely the only one, and usually I'm right. That's why Jacquard exists as a standalone library, rather than as part of Weaver, and it's why I do ultimately plan to extract the editor from Weaver as its own library as well. Rust needs this. GPUI works great so far, Zed is a great editor, but it's never going to really target browsers, nor should it. How tightly to couple that version to Markdown I'm not sure. This editor is primarily the way it is in part because it does something arguably harder than Tiptap, map an editable linear text buffer to HTML in real time. That's good for some things but not others, but the biggest one is Markdown, though I guess it probably works for EMACS org-mode docs as well, and MediaWiki's format, and so on. And of course nothing prevents it from working on a JSON block-based format like Tiptap's or Leaflet's (both Prosemirror under the hood), depending on the way the library version ends up being designed.

Next Steps

Ultimately, I'm still far from done with Weaver's editor. This will likely be the most picky part of the entire project by a long shot, causing by far the most visible usability issues and hindering adoption the most. But honestly I'm glad I did, in part because this means I'm not having to navigate adding extensions to TipTap or its beta-level support for actual bidirectional Markdown conversion, a feature which Weaver's editor simply gets inherently by virtue of being built for Markdown from the beginning. I'll keep improving it as I build out the rest of the platform. Hopefully as things get usable, people start, well, using it.